AWOL in America:

When Desertion is the Only Option KATHY DOBIE / Harper's Magazine v.310, n.1858 1mar2005

An AWOL Navy man was arrested ... as he brought his pregnant wife to the hospital.... Roberto Carlos Navarro, 20, of Polk City [Florida] was charged as a deserter from the U.S. Navy.... Navarro became disenchanted with the constant painting and scraping of ships after two years in the Navy.

—The Ledger,

April 2, 2004

A 17-year-old was turned over to the Department of Defense last week after Bellingham police discovered the teenager, involved in a traffic accident, was allegedly a deserter from Army basic training.

—The Boston Globe,

August 12, 2004

I am seriously considering becoming a deserter. I am sorry if there are other military moms ... that look poorly on me for thinking this way but ... I WILL NOT LEAVE MY LITTLE BABY.

—Online post to BabyCenter.com,

November 21, 2004

The GI Rights Hotline

(800) 394-9544

(215) 563-4620

Fax (510) 465-2459

Mailing Address:

405 14th Street Suite 205

Oakland, CA 94612

girights@objector.org

http://girights.objector.org AWOL, French Leave, the Grand Bounce, jumping ship, going over the hill—in every country, in every age, whenever and wherever there has been a military, there have been soldiers discharging themselves from the ranks. The Pentagon has estimated that since the start of the current conflict in Iraq, more than 5,500 U.S. military personnel have deserted, and yet we know the stories of only a unique handful, all whom have publicly stated their opposition to the war in Iraq, and some of whom have fled to Canada. The Vietnam war casts a long shadow, distorting our image of the deserter; four soldiers have gone over the Canadian border, looking for the safe haven of the Vietnam years, which no longer exists: there are no open arms for such refugees and almost no possibility of obtaining legal status. We imagine 5,500 conscientious objectors to a bloody quagmire, soldiers like Staff Sergeant Camilo Mejia, who strongly and eloquently protested the Iraq war, having actually served there and witnessed civilians killed and prisoners abused, and who was subsequently court-martialed, found guilty of desertion, and given a year in prison. But deserters rarely leave for purely political reasons. They usually just quietly return home and hope no one notices.

Last summer, I read a news account of a twenty-one-year-old man caught by the police climbing through the window of a house. It turned out to be his house, but the cops found out he was AWOL from the Army and arrested him. That story, in all its recognizable, bungling humanity, intrigued me. It brought the truth of governments waging war home to me in a way that stories of combat had not—in particular, how the ambitions and desires of powerful men and women are borne by ordinary people: restless scrapers and tomboys from West Virginia, teenage immigrants from Mexico, and juvenile delinquents from Indiana; randy boys and girls, and callous ones; the stoic, the idealist, the aimless, the boastful and the bewildered; the highly adventurous and the deeply conformist. They carry the weight.

After reading the story of the AWOL soldier sneaking into his own house, I contacted the G.I. Rights hot line, a national referral and counseling service for military personnel, and on August 23, 2004, I interviewed Robert Dove, a burly, bearded Quaker, in the Boston offices of the American Friends Service Committee, one of the groups involved with the hot line. Dove told me of getting frantic calls from the parents of recruits, and of recruits who are so appalled by basic training that they "can't eat, they literally vomit every time they put a spoon to their mouths, they're having nightmares and wetting their beds." Down in Chatham County, North Carolina, Steve and Lenore Woolford answer calls from the hot line in their home. Steve was most haunted by the soldiers who want out badly but who he can tell are not smart or self-assured enough to accomplish it; the ones who ask the same questions over and over again and want to know exactly what to say to their commanding officer. The G.I. Rights hot line introduced me to deserters willing to talk, and those soldiers put me in contact with others.

I met my first deserters in early September and over the next four months followed some of them through the process of turning themselves in and getting released from the military. They came from Indiana, Oregon, Washington, California, Georgia, Connecticut, New York, and Massachusetts. I met with the mother and sister of a Marine who was UA (Unauthorized Absence, the Navy and Marine term for AWOL) in the mother's home in Alto, Georgia, and at the Quantico base in Virginia one Sunday afternoon I met with eight deserters returned to military custody, members of the Casualty Platoon, as the Marines refer to them, since they are "lost combatants." One of the AWOL soldiers, Jeremiah Adler, offered to show me the letters he had written home from boot camp; a Marine called with weekly reports from Quantico where he awaited his court-martial or administrative release. Through these soldiers, and the counselors at the G.I. Rights hot line, I discovered that the recruiting process and the training were keys to understanding why soldiers desert, as is an overextended Army's increasingly strong grip on them.

Since the mid-1990s, the Army has been quietly struggling with a manpower crisis, as the number of desertions steadily climbed from 1,509 in 1995 to 4,739 in 2001. During this time, deserters rarely faced court-martial or punishment. The vast majority—94 percent of the 12,000 soldiers who deserted between I997 and 2001—were simply released from the Army with other-than-honorable discharges. Then, in the fall of 2001, shortly after 9/11, the U.S. Army issued a new policy regarding deserters, hoping to staunch the flow. Under the new rules, which were given little media attention, deserters were to be returned to their original military units to be evaluated and, when possible, integrated back into the ranks. It was not a policy that made the hearts of Army officers sing. As one company commander told DefenseWatch, an online newsletter for the grass-roots organization Soldiers For The Truth, "I can't afford to baby-sit problem children every day."

According to DefenseWatch, in the first few months after the policy went into effect, 190 deserters were returned to military control, 89 of those were returned to the ranks, and 101 were discharged. Statistics at the end of the military fiscal year showed the desertion numbers dropping slightly, due, at least in part, to the new policy, which reintegrated almost half the runaways back into their units. It wasn't that fewer people were leaving the military, just that fewer people were able to stay gone.

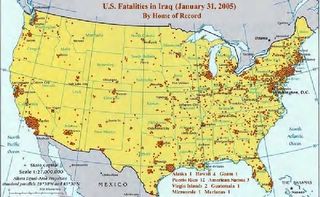

Then we invaded Iraq, and as the war there rages on, the military has had to evacuate an estimated 50,000 troops: the dead and the wounded, combat- and non-combat-related casualties. Those soldiers must be replaced—and we're committed to sending in even more. The pressure to hold on to as many troops as possible has only increased, as is painfully evident in internal memos such as this one from Major General Claude A. Williams of the Army National Guard, dated May 2004: "Effective immediately, I am holding commanders at all levels accountable for controlling manageable losses." The memo goes on to say that commanders must retain at least 85 percent of soldiers who are scheduled to end their active duty, 90 percent of soldiers scheduled to ship for Initial Entry Training, and "execute the AWOL recovery procedures for every AWOL soldier." The military has issued stop-loss orders, dug deep into the ranks of reservists and guardsmen, extended tours of duty, and made it harder for recruits and active-duty personnel to get out through administrative means. According to the military's own research, this will result in more people going AWOL.

In the summer of 2002, the U.S. Army Research Institute for the Behavioral and Social Sciences released a study titled "What We Know About AWOL and Desertion." "Although the problem of AWOL/desertion is fairly constant, it tends to increase in magnitude during wartime—when the Army tends to increase its demands for troops and to lower its enlistment standards to meet that need. It can also increase during times, such as now, when the Army is attempting to restrict the ways that soldiers can exit service through administrative channels." In other words, close the door, and they will leave by the window.

At the G.I. Rights hot line, the desperation is obvious; the number of people calling in for help has almost doubled from 17,000 in 200I to 33,000 in the last year. The majority of the calls are from people who want out of the military—soldiers with untreated injuries or urgent family problems, combat veterans who have developed a deep revulsion to war, National Guardsmen primed to deal with hurricanes, blizzards, and floods but not fighting overseas, and inactive reservists who have already served, started families and careers, and never expected to be called up again. And there are recruits—many, many recruits—who have decided, in a sentiment heard hundreds of times by the people manning the phones, "The Army's just not for me." Some of these callers were thinking about going AWOL; others had already left and wanted to know what could happen to them and what they should do next.

Soldiers who go AWOL have either panicked and see no other way out of their difficulties or are well-informed and know that deserting is sometimes the quickest, surest route out of the military. A soldier may not be eligible for a hardship or medical discharge, for instance, but he knows he wants out. He may not even be aware of the discharges available to him. Young, raw recruits, in particular, know only what their drill sergeants tell them. Counselors at the G.I. Rights hot line describe cases in which a recruit will ask about applying for a discharge and be told flatly by his drill sergeant, "Forget about it. Don't even think of applying. You're not getting out." Conscientious-objector applications have more than tripled since operations began in Iraq, but they take on average a year and a half to process, and then, quite often, are denied.

In the Army study, which examined data from World War II, Korea, Vietnam, and the years 1997-2001, it was found that deserters are more likely to be younger when they enlist, less educated, to come from "broken homes," and to have "engaged in delinquent behavior" prior to enlisting. In other words, they are both vulnerable and rebellious. During the Vietnam war, enlisted men were far more likely to desert than those who were drafted. Perhaps they had higher expectations of Army life, or perhaps a man who volunteers for service feels like he has some sense of control over his fate, a feeling a draftee could hardly share. Only 12 percent of the Vietnam-era deserters left specifically because of the war, according to the same study. Then, as now, most soldiers take off because of family problems, financial difficulties, and what the Army obliquely calls "failure to adapt" to military life and "issues with chain of command." Almost all of the deserters I spoke to described the kind of person they thought succeeded in the military as "an alpha male type who can take orders real well," as one Marine put it. "If you can't do both? Don't join." Physical aggression and mental docility might seem an unlikely pairing, but as the military historian Gwynne Dyer wrote in his book titled, simply, War, "Basic training has been essentially the same in every army in every age, because it works with the same raw material that's always there in teenage boys: a fair amount of aggression, a strong tendency to hang around in groups, and an absolute desperate desire to fit in."

It's hard for me to be myself here. There's no room for dissent among the guys. Everywhere you listen you hear an abundant amount of B.S., a few beds over an obnoxious redneck has a crowd around him as he details a 3 some that he recently had. The vocabulary is much different here. The bathroom is called the latrine, food is called chow, women are hitches, sex is ass. . . . These people want to go to war and kill. It is that simple."

—From a letter home,

Jeremiah Adler

Jeremiah Adler arrives at my door in Brooklyn in late September, four days after he escaped Fort Benning, Georgia, with another Army recruit. At ten at night, while a friend on guard duty looked the other way, the boys took off out of the barracks, making a thirty-yard dash into the surrounding forest. They had no clue as to where they were. After an hour they heard sirens blasting, and then the baying of dogs. They spent five hours in the woods, following a bright patch in the sky that they rightly assumed to be the city of Columbus. When they finally reached the road, they saw cop cars zipping past them, lights flashing in the dark. It was terribly exciting, though the morning he arrives at my house he seems spent. Jeremiah and I had spoken for the first time the day before. He was hiding out at a friend's house in Atlanta, ready to hop the next plane home to Portland, Oregon, but he agreed to meet with me in New York first.

Jeremiah is slight, and his blue-green eyes seem unusually large, though that could be the effect of his shorn head. He has full lips and a fine-boned face that could easily become gaunt. He's eighteen, a deeply earnest eighteen, with a dry sense of humor. He has an odd habit for someone so young of sighing often, and wearily. He's also very hungry. We order a cheese pizza because he does not eat meat.

When Jeremiah announced his intention to join the military he took everyone who knew him in Portland by surprise. "He was raised in a pacifist, macrobiotic house," his mother exclaims. "He went to Waldorf schools. Here is a kid who's never even had a bite of animal flesh in his life!" Jeremiah had protested the Iraq war, in fact. He spent most of his senior year in high school convincing his family and what he and his mother call his "community"—a tightly knit group of families connected by the Portland Waldorf School and Rudolf Steiner's nontraditional philosophy of education—that joining the military was the right thing for him to do.

In the spring of his senior year, Jeremiah went on a "vision quest," hiking into an area called Eagle Creek, which was still covered in snow. There he made a video explaining his reasons for joining the Army. He sits on the ground facing the camera but looking off into the woods as he talks. He starts by making a case for the military being a tool for change, a possible force for good. But, "if you have a bunch of bloodthirsty young men with an I.Q. of twenty-three in the military, that's what the military's gonna be—until other people, other intelligent people with morals and values and convictions and ideals [join up]. Most people hate the military. Is the answer to distance yourself as far as you can and just protest all the time? What am I doing? I don't know anyone in the military. Neither do any of you. It takes a lot more balls for me to join the military than it does for one of you guys to go to a forty-grand liberal-arts school. Is that a huge step? You're gonna be around more open-minded people like yourself. You're not gonna experience any diversity there."

In this taped explanation he leaves out one reason for joining the Army, a reason that perhaps was too amorphous to put into words, or too personal, not something he felt the folks at Waldorf would understand. "My mom was single until I was eight years old," he tells me. "My entire life I was raised sensitive and compassionate. I have a craving for a sense of machoness, honestly. A sense of toughness." He remembers the first time he thought the military was "cool"—watching Top Gun at ten years old. Then in his senior year of high school, the recruiting commercials became a siren call. "I mean, it's an ingenious marketing campaign. It goes straight to an eighteen-year-old male's testosterone. You see them and you're almost sexually aroused," he says. He wanted to kick past the cocoon of family and community, to know how other people thought and lived. He wanted a coming-of-age ritual—his vision quest, which had ended with the insight "solitude sucks," didn't quite fill the bill. He wanted to become a man. Jeremiah took a year convincing his friends, family, and community, and yet within seventy-two hours of arriving at Fort Benning he was writing a letter home that began, "Hello All, You have got to get me out of here."

The recruits arrived at Reception Battalion at Fort Benning on September 16 close to midnight, completely disoriented. During the next seven days they were introduced to military life: First, their heads were shaved, a ritual that signifies the loss of one's individual identity, and was historically used to control lice and identify deserters. Then the recruits were issued boots, gear, and military I.D. They were taught how to march and stand at attention, made to recite the Soldier's Creed again and again, yelled at, incited, insulted, and then shipped to basic training; that is, put on a bus and sent to a training barracks at another location in Fort Benning.

The first day of Reception, the recruits should have been so busy and harassed that they wouldn't have had time for second thoughts or regrets, but Hurricane Ivan was sweeping through Georgia, and they were confined to their barracks—104 young men, all keyed up, all on edge, about to embark on some mysterious journey, some awesome transformation that involved uniforms, mud, and guns. There was a constant jockeying for power, fights narrowly averted, a lot of enthusiasm for battle, for killing, or at least the pretense of enthusiasm. When Jeremiah suggested it might be better to wound someone than to kill him, he was quickly put in his place. "Fuck that. I'm putting two in the chest, one in the head just like I'm going to be trained to do."

The men in the barracks were whiter, poorer, and less educated than Jeremiah had expected. Guys who could barely read were astonished that Jeremiah had enlisted even though he'd been accepted at the University of Oregon. Skin-heads, exskinheads perhaps (since active participation by soldiers in extremist groups is prohibited), showed off their tattoos—one had been told by his recruiter to say that his swastika tattoo was a "force directional signal." There were guys who had done jail time, though Jeremiah quickly adds, "Not that they're bad people by any means, but it kind of shows you the type of person they're recruiting."

The next day, a sergeant addressed the recruits with a speech that Jeremiah says he'll never forget. "You know, when I joined the Army nine years ago people would always ask me why I joined. Did I do it for college money? Did I do it for women? People never understood. I wanted to join the Army because I wanted to go shoot motherfuckers." The room erupted in hoots and hollers. A drill sergeant said something about an Iraqi coming up to them screaming, "Ah-la-la-la-la!" in a high-pitched voice, and how he would have to be killed. After that, all Arabs were referred to by this battle cry—the ah-la-la-la-las. In the barracks, they played war. One recruit would come out of the shower wearing a towel on his head, screaming, "Ah-la-la-la-la!" and the other recruits would pretend to shoot him dead. Jeremiah thought, "Oh my God, what am I doing here?"

That evening he wrote his first letter home, beginning with the word "Wow."

"I'm horrified by some of the things that they talk about. If you were in the civilian world and openly talked about killing people you would be an outcast, but here people openly talk about it, like it's going to be fun." In his second letter, written while he was doing guard duty, he tells his parents how sad the barracks are at night. "You can hear people trying to make sure no one hears them cry under their covers."

On his third day, Jeremiah went to one of the drill sergeants and told him, "I'm sorry, the military's not for me. For whatever reason, I'm not willing to kill. I had the idealistic view that it was more than that, and I realize, since coming here, that it's not." The sergeant stared at him. "Do you know what would happen if you came in here and talked to me fifty, a hundred years ago?"

"Yeah, but we're not living back then," Jeremiah replied. The sergeant said that was a shame, because if he had a 9-millimeter pistol, he'd shoot Jeremiah right then and there. The sergeant dared Jeremiah to refuse to ship, saying he would be sent to jail, that he, personally, would make an example of him.

So Jeremiah cooked up a plan with another unhappy recruit to pretend they were gay. That plan went about as badly as it could have—five drill sergeants questioned them, called them disgusting perverts, but refused to discharge either Jeremiah or his friend. Jeremiah was now stuck in one of the most macho and homophobic environments as a gay man, or, more bewilderingly, as a fake gay man. He had tried to get help from the military chaplain, who cited Bible passages proving that God was against murder, not killing, and told Jeremiah that Iraqis were running up to American troops requesting Bibles.

In his last letter home, written on his sixth day, Jeremiah's handwriting disintegrates; "HELP ME" is scrawled across one page. He was due to ship to basic training in the morning. He had decided to refuse. "I've heard that they try to intimidate you, ganging up on you, threatening you. I heard that they will throw your bags on the bus, and almost force you on. See what I am up against? I have nothing on my side.... I am so fucked up right now. ... I feel that if I stay here much longer I am not going to be the same person anymore. I have to GO. Please help.... Every minute you sit at home I am stuck in a shithole, stripped of self-respect, pride, will, hope, love, faith, worth, everything. Everything I have ever held dear has been taken away. This fucks with your head. . . . This makes you believe you ARE worthless shit. Please help. By the time you get this, things will be worse."

After getting some information from his mother on a secretive call home, Jeremiah wrote a letter requesting Entry Level Separation from the Army, citing his aversion to killing. Entry Level Separation, which exists for the convenience of the Army, allows for the discharge of soldiers who are obviously not cut out for military service. The Army has to provide an exit route for inept, unhealthy, depressed, even suicidal soldiers, but at the same time it doesn't want to open what might turn out to be floodgates, so soldiers cannot themselves apply for ELS, and rarely even know about its existence. The Reception Battalion commander told Jeremiah that if he refused to ship, he would do everything in his power to court-martial him. Then the drill sergeants had their turn. One in particular was apoplectic. "He started screaming at me about how killing is the ultimate thrill in life and every single man wants to kill. Regardless of what you think you believe, it's every man's job to kill, it's the greatest high, it's our animal instinct, our animal desire."

When he refused to ship (he locked his duffel bag to his bed so it couldn't be thrown on the bus), Jeremiah was sent to Excess Barracks. About twenty other recruits were there, each of them trying to get out. It was at Excess Barracks that Jeremiah first got the idea to go AWOL, because there were people there who had done it already. On his ninth day at Fort Benning, he and another recruit, Ryan Gibson, decided to leave. They got all suited up—"a Rambo-like moment" is how Jeremiah describes it. "I'm not gonna lie, we were really excited," he says. "We were finally going to be able to go out into the woods and do something. Even if the only commando stuff we ever did in our entire Army career was escaping from the Army, we were still excited about it."

When Ryan arrived home in Indiana, his mother threatened to report him to the police unless he returned to Fort Benning. So Ryan did return, but he left again two days later, this time taking two other recruits with him. When Jeremiah arrived home in Portland, he told his mother, "Well, Mom, I guess I'm going to have to find a different way to become a man besides learning to kill."

Jeremiah is hardly the only recruit to arrive at basic training or boot camp and realize, for the first time, that he is there to learn how to kill. And that he can't or won't do it. Many civilians wonder how that can be: They're joining the Army, for God's sake, they've enlisted in the Marines, what did they expect? It is too simple an answer just to say that the recruiters don't mention killing, though they don't, and that they sell the military as a career or educational opportunity to high schoolers, which they do. You have to understand that after all the soft, inspiring talk of educational opportunities, financial bonuses, job skills, cool gear, and easy sex from uniform-loving girls and German prostitutes, recruits arrive at boot camp and are assaulted by a completely different reality. Basic training is a shock, and purposefully so. In a matter of weeks the military must take teenagers from what Gwynne Dyer calls "the most extravagantly individualistic civilian society" and turn them into soldiers; that is, selfless, obedient fighters with an intense loyalty to each other, for ultimately that is why they will risk death, not for their country or some high-flown ideal but for their comrades. "We" must replace "I." Most importantly, the military must turn them into killers, for that is how you win battles, and how you survive them.

Despite our entertainment industry telling us otherwise, it is not easy to kill. In his ground-breaking and highly influential study of World War II firing rates, S.L.A. Marshall, a World War I combatant and chief historian for the European Theater of Operations during World War II, interviewed soldiers fresh from battle and found that only 15 to 20 percent of the combat infantry were willing to fire their weapons, and that was true even when their life or the lives of their comrades were threatened. When Medical Corp psychiatrists studied combat fatigue cases in the European Theater, they found that "fear of killing, rather than fear of being killed, was the most common cause of battle failure in the individual," Marshall reported. Marshall's methodology is now in question, but his findings have been replicated in studies of Civil War and World War I battles, even in recreations of Napoleonic wars. And the effect of his findings on the military has been profound. As Lieutenant Colonel Dave Grossman notes in his book On Killing: The Psychological Cost of Learning to Kill in War and Society, "A firing rate of 15 to 20 percent among soldiers is like having a literacy rate of 15 to 20 percent among proofreaders. Once those in authority realized the existence and magnitude of the problem, it was only a matter of time until they solved it."

By the Korean War, the firing rate had gone up to 55 percent; in the Vietnam war, it was around 90 to 95 percent. How did the military achieve this? As Grossman writes, "Since World War II, a new era has quietly dawned in modern warfare: an era of psychological warfare—psychological warfare conducted not upon the enemy, but upon one's own troops. ... The triad of methods used to achieve this remarkable increase in killing are desensitization, conditioning, and denial defense mechanisms."

Training techniques became more realistic and varied. Soldiers no longer stood and fired at a nonmoving target. They were fully suited up, down in foxholes, and shooting at moving targets, targets that resembled other humans. Simultaneously, the "enemy," whether North Korean, North Vietnamese, Russian, or Arab, was purposefully dehumanized. Killing people was described graphically, and with relish. As Dyer notes, most recruits realize the bloodthirsty talk of drill sergeants is hyperbole, but it still serves to desensitize them to the suffering of an "enemy."

So the answer to the question "How could they not know that they were there to learn how to kill?" is another question: "How could they even begin to comprehend what that meant?" Before they've even seen combat, these young men and women, most of them teenagers, will be pushed to break through a psychological, cultural, and moral resistance to killing, an experience that is hard to imagine. A twenty-three-year-old deserter from Washington State, whom I'll call Clay, since he's still AWOL, says, "'Stressful' is not the word. It's an understatement. It tears at your mind." Clay, who went AWOL in November, was excruciatingly aware of the effect of his training: "After they broke me down, I was having a lot of conflicts with what they were trying to build me back up into. I mean, good Lord, these people told me, if need be, I might have to kill children."

Clay joined the Army to get away from what he calls "a militant AA group" and a troubled relationship with a girlfriend. He was working off the books for a small fencing company, and the Army recruiter was "throwing all this money at me." In five weeks he wrapped up his messy life—gave notice on his apartment, quit his girlfriend and his AA group, lost sixty pounds, took and passed his GED—and swore in to the U.S. Army.

By the sixth week of training, Clay realized not only that he could kill but that he wanted to. "Spiritually and mentally, man, I was off. I wanted to kill something. Mainly the drill sergeants, hut it was had. I was very angry. I started to see the process within myself, that transition from civilian to mindless killer. It just didn't sit right with me. And it scared me." Clay decided to leave. A high-ranking but highly embittered NCO actually smuggled him off base.

That soldiers flee out of fear of combat is another myth; not that some don't, but they are, strangely enough, a minority. Of the deserters I talked to, only Clay mentioned his fear of death. After his drill sergeant showed his platoon photos of an American lieutenant blown to bits, splattered all over the side of a Humvee, "no piece of him bigger than a cigarette pack," Clay suddenly thought about being around to raise a family. "And I started thinking about the possibility that I might not come back." He's gone AWOL twice now. He left from basic training, returned home, and twenty-six days later turned himself in at Fort Lewis, Washington, where he met Jeremiah, who gave him my phone number. From there he was sent to Fort Sill, Oklahoma. At Fort Sill he was told that he would be shipped back to Fort Benning, so he took off again. He had turned himself in too soon.

AWOL in America: When Desertion is the Only Option KATHY DOBIE / Harper's Magazine v.310, n.1858 1mar2005

After thirty days of being AWOL, a soldier is dropped from the rolls and classified as a deserter—administratively, not legally, for that takes a court-martial. At that point, a federal warrant is issued for his arrest. The Army doesn't have the manpower to chase and apprehend deserters, so unless they get picked up for some other offense—stopped by the local cops for running a red light, for instance—they can often live life unhindered (but not necessarily unhaunted) for weeks, months, even years. Recently in New York City, a forty-three-year-old Marine deserter got into an argument with a deli owner about the difference between smoked and honey-basted turkey. The deli owner called the Marine a "nigger." The Marine told him to step outside. They were slugging it out on the sidewalk when the cops pulled up. They ran the Marine's driver's license, found the federal warrant for his arrest, and called the Marines, who came and got him and drove him down to Quantico, where he now awaits processing. He'd been AWOL for twenty-four years.

Once a deserter is apprehended or turns himself in, he can be returned to his unit, or court-martialed and given jail time, or given nonjudicial punishment and an other-than-honorable discharge. As a rule of thumb, the less time and money the military has invested in someone, the less interested it is in keeping that person. If you're going to leave, then, leave sooner rather than later, and when you leave, stay gone long enough to be dropped from the rolls. If you turn yourself in before being dropped from the rolls, you'll be returned to your command. And it's always better to turn yourself in than to be caught—you want to show that your intention wasn't to stay gone forever. So you have to prove that you are dead serious about leaving the military while simultaneously proving that you weren't planning on leaving for good.

Matt Burke, a Navy veteran and Army deserter, whom I met in October, left the military because of an injury, a recruiter's lie, and because there was better pay—and working conditions—somewhere else. Matt is pro-military, pro-Bush, though, he says, "Your readers won't want to hear that, I'm sure." He describes his recent court-martial as the Army's chance to ream him and his subsequent jail time as "interesting." He has a bland, limited vocabulary for the good times in his life, and a much grittier one for the bad—getting shafted, screwed, kicked in the nuts. He tells his story as straight as he can, without much emotion and no self-pity. He doesn't want his real name used because only his immediate family knows about his going AWOL, and his parents thought he was "as dumb as shit" to desert the Army.

Blond, trim, seemingly buttoned-down but with a gleam in his eye, Matt is the youngest son of a large Irish-Catholic family. He says frankly that he had a "bad upbringing," and by that he means he was raised to care about job security above all else. He joined the Navy straight out of high school, at seventeen. He wasn't a good student; there was little chance of his getting into a decent college and no chance of a scholarship. He had family members in the military; it wasn't an unfamiliar option for him. He did his four years of active duty and loved it. When he returned to his New England hometown, he attended college, where he studied business. After two years as an accountant in the civilian world, he began to miss the military. So he decided to sign up for the Army's Officer's Candidate School.

Matt had one worry. He knew that after three months of basic training and then another three at OCS, the chances of getting injured were high. He asked the recruiter what would happen if he got hurt and couldn't make it through OCS. He was determined to serve in the Army only as an officer; he had already done his time, and he now had a college education, a good-paying job. The recruiter told him that because of his prior service, he wouldn't have to serve the remainder of his three-year contract; he would be discharged. Later, Matt would kick himself for not getting it in writing. "So that's the thing that got me screwed, trusting him," Matt says. He thought the recruiter wouldn't lie to him: he wasn't some green high school kid. "I thought me being in prior service, he'd recognize that, and he knows that I know he's a salesperson basically. But he still ended up giving me the shaft."

At the G.I. Rights hot line they've heard hundreds of stories involving recruiters' lies. Jeremiah was told he could attend college after he finished basic training, and that he wouldn't be deployed until he graduated. One of the most common lies told by recruiters is that it's easy to get out of the military if you change your mind. But once they arrive at training, the recruits are told there's no exit, period—and if you try to leave, you'll be court-martialed and serve ten years in the brig, you'll never be able to get a good job or a bank loan, and this will follow you around like a felony conviction. This misinformation may keep some scared and unhappy soldiers from leaving—some may even turn out to be suffering from no more than a severe bout of homesickness—but it pushes others to the point of desperation. They purposefully injure themselves or become clinically depressed; they try to kill themselves or set out to fail the drug test; or they lie, saying they're gay, suicidal, asthmatic, or murderous. And, of course, they go AWOL.

None of this behavior, the lies or the pressure tactics, is particularly surprising. Recruiters are under tremendous pressure to meet year-end recruiting goals, which are essentially set by Congress. (Congress mandates the actual number of soldiers required to be on active duty at the end of the recruiting year.) Failure to meet their "mission" can affect job promotion, pay, even the ability to stay in the Army until retirement. When the fiscal year ends in September, if Recruiting command hasn't met its quota, it shifts the ship dates of soldiers in the Delayed Entry Program (DEP)—soldiers due to ship to training in October and November often are rescheduled to ship in the last week of September. Recruiting command can then report favorably to Congress, but the recruiters have to scramble even harder to make up for those lost numbers in the coming year.

What is puzzling is the fact that so many people believe the recruiters, believe even the most outrageous lies. High schoolers and their parents. Diane Stanley, the mother of a UA Marine named Jarred whom I met with in her trailer home in Alto, Georgia, told me that the recruiter promised her and her son that he wouldn't be sent overseas. He would, in fact, be stationed close to home in Kentucky. We were at war in Iraq, and still they believed this. The recruiter was sitting at their kitchen table, drinking her coffee, a man she describes as being "super nice." He told the lie then and repeated it every time she asked for reassurance. She trusted him.

Most people simply have a hard time wrapping their minds around the fact that someone would look straight at them and tell a bald-faced lie, especially when that someone is in uniform, representing the United States government, and has visited their homes and been "a part of our family," as Jeremiah's mother puts it. The recruiter had often dined at the Adler house; he attended Jeremiah's high-school graduation. And there's no denying that many parents who want their children, particularly their sons, to grow up and find some sense of purpose and responsibility have magical thinking when it comes to the military.

When I spoke with Douglas Smith of the U.S. Army Recruiting Command's Public Affairs Office, he said he found the lies told to Jeremiah, Matt, and Jarred far too outrageous to believe that any recruiter would tell them. Smith told me that recruiters rely on a good relationship with the community, and recruiting itself relies on satisfied, enthusiastic graduates of basic training promoting the service back home. Recruiters may talk of "possibilities," Smith suggested, that a recruit may hear as promises, such as large student loans that are available only to qualified recruits. His advice was that recruits need to read their contracts carefully before signing them; if the recruiter's "possibilities" are not written into the contract, they don't exist.

In the last few weeks of basic training, Matt pulled a knee ligament, but he "sucked it up" and graduated. At OCS, his knee injury grew worse until he was no longer able to run. After a few visits to sick bay, he was booted out of OCS for missing too many training days. He was put in a holding company, and there he waited with other injured or rejected OCS candidates to receive orders to go to enlisted training. He was Army property. He had three years of a contract to fulfill. He would be trained in a Military Occupational Specialty (MOS) that fit the needs of the Army—these days the military seems to be short MPs and truck drivers. He was angry.

When Matt went home on leave, he didn't go back. After discussing his case with people on the G.I. Rights hot line, he waited the thirty-plus days until he was dropped from the rolls and declared a deserter, then he traveled to Fort Sill, Oklahoma to turn himself in. The treatment at Fort Sill was "very routine, very professional," Matt says. Except for him and one other young recruit, all of the other deserters were quickly processed out. Matt's command wanted him back at Fort Benning so that they could court-martial him. "I was from an OCS battalion, and I think at that same time the war in Iraq was peaking, so I think they felt they couldn't just let me go. They had to bring me back and give me the shaft as best they could, to set an example."

He was flown to Fort Benning, waited for a month and a half for his court-martial, and after a ten-minute proceeding was given a one-month jail sentence and an other-than-honorable discharge. He served his time in a county jail, cheaper for the Army than shipping him to the nearest Army brig in Pensacola, Florida. There, Matt says, he was locked up with a bunch of "colorful characters"—drug dealers with meth labs in their basements, indicted murderers.

Jason Lane tramps out of the forest wearing a blue bandanna, a black sweater, and a bulky Marine-issue backpack. He's neither short nor tall, more thick than thin, dark-haired, dark-eyed, with an expressive face. "Hey! How yah doin'?" His voice booms, as if he's speaking through a megaphone, and in any given word there are more inflections than there are syllables. It's a strange moment. Meeting a Marine deserter in the Virginia woods fits my dramatic image of the situation, but the Marine himself, an affable nineteen-year-old from Connecticut with a high tolerance for chaos, seems entirely familiar.

It's a brilliant September day in Triangle, Virginia; cool, bright air, a piercing blue sky. At the picnic area of Prince William Forest Park, one couple in business suits eats their lunch and an old man reads a newspaper. Otherwise, the park seems spectacularly empty of humans, all I7,000 acres of it. One mile away is the big statue of Iwo Jima that marks the entrance to the Quantico Marine base. Jason, whose name has been changed because he is currently in military custody, deserted the Marines on August I, leaving Camp Geiger in North Carolina and heading home to Connecticut. When he decided to turn himself in, he chose Quantico because he heard deserters were treated more fairly there than at Camp Geiger. Jason took a bus down here, arriving yesterday afternoon, but instead of walking to the base, he walked into the forest. He needed some time, he says.

Jason's mother married a Navy man, but she adores the Marines, and she always told Jason he would make a great one. Right before he went UA, Jason tried to explain to her that you could be good at something and still not want to do it. They were so proud at his graduation from boot camp, he tells me. And now? "It's horrible," he says. "It's very horrible. I can't even face them. It kind of makes me wish I never even left." Still, he calls his decision to join the Marines last winter "stupid," and his decision to go UA "stupid but right." At the end of the day, I bought him some snacks and Gatorade and left him at the picnic area as the sun was going down. The temperature dropped hard that night, so he spent it crouched under a hand dryer in the rest room, reaching up to turn it on every time it shut off. On the third night, Jason left the forest and simply started to walk—through the town of Triangle and on to Dumfries, and beyond, and then back again, CD earphones clamped on his head, Iron Maiden blasting, making up fantastic stories and movie scenes that he would think about jotting down in the notebook he kept in his backpack. For the next seven nights, Jason would begin walking as the sun went down, and he would walk until dawn, keeping himself warm. Before the sun rose, he would lie down on the bleachers at a local ballpark. On my three visits to Virginia, I'd buy him dinner and cigarettes, and we'd talk about his family, the Marines, the adventures he was having living on the streets. I came to admire the lengths Jason would go to avoid that moment of surrender.

Jason is always cheerful when I see him, and like many cheerful people, he has a tendency toward depression, which he fights with caffeine, cigarettes, that booming voice, a hale-and-hearty manner. In high school Jason liked to perform in front of groups, clown around, stir people up. But he's also a dreamer, someone who can't think in a straight line. He'd love to make movies someday, something fantastic and allegorical. Jason has a passionate belief in Christ, and no fear of death because of that, he says. He seems a completely unlikely candidate for boot camp.

Jason had dropped out of high school when the Marine recruiter called. He had what he calls "a shitty relationship with his parents"; it made him unhappy. He had no diploma, no direction, only vague dreams of acting and directing films. The recruiter offered a definite course—both a compelling reason to get his high-school diploma and a plan for the near future. As his enlistment date approached, though, Jason felt less and less like going. "I was trying to ask people, `You think I should cop out of this now while I got a chance?"' But Jason's passivity, his inability to think clearly, to see the outlines of another future—how does a high-school dropout go about becoming a film director?—left him wide open to currents that were far too strong. Jason simply rode those currents straight to Parris Island. "I had the mentality—I made the commitment, I'm gonna give it a shot," he explains. "How much can it really hurt?"

Boot camp was great, he says, though at the time it was awful. He hated every minute of it, especially being so completely caught in a bleak and grueling present that there was nothing to look forward to but chow. He loved and admired his drill instructors, never doubting that they had his best interests at heart, and he was terribly proud on graduation day. Later he would tell me that it was the happiest day of his life.

It was when he started Infantry School at Camp Geiger in North Carolina that Jason's resolve, never strong to start with, folded. At boot camp, he got along with all the other recruits; they were harassed and beaten down and completely unified. But at Camp Geiger his fellow Marines were "just your typical man pig assholes," Jason says, and then goes to great effort to explain a certain character type to me. "You gotta understand, people who typically join the Marines have a certain mentality. They have to prove something. Because of that mentality, this is what you get when they get confidence, you get this cocky, arrogant, look-at-me-now type of thing. And I'm sitting there saying, I'm not going to the end of the road with these guys. I will gladly fight and die for my family, my friends, and for my country. I will not fight and die with people that I don't like."

In his fifth week of training his leg got infected. His combat instructors thought they knew what it was—cellulitis—but told him it wasn't all that serious yet and to wait three days for treatment until the base clinic opened. His leg swelled until he could no longer put on his boot. Still, he was given a twenty-four-hour walking post. On Sunday he was rushed to the hospital, where he stayed for a week. When he returned, he had to keep his leg elevated, and the drill instructors treated him as if he were a shirker. The final straw in this series of events that Jason would simply call "bullshit" was when they refused to give him weekend liberty because he hadn't passed a test that he couldn't have taken anyway, because he was in the hospital when it was given.

Two themes run through Jason's story, very common ones in the stories of AWOL soldiers. Jason was not a young man who found himself appalled by the training, by the notion of killing. He was someone who was ambivalent about joining in the first place and then objected not to the hard work or the discipline but to what he considered unfair treatment. "Even though it sucks right now, it still feels like I did the right thing," he says of his decision to desert. "For one, I did something I shouldn't have done by joining. For two, I believe you should always stand up for what you believe in, and I don't believe that I should've been treated like that for my leg."

People leave civilian jobs when they're treated unjustly, and no civilian boss holds your mortal life in his or her hands. When you enter the military, you're not arriving at some day job, a job that requires only a piece of you and your time, a job you can easily leave. The military is your new family; indeed, during training, it's your entire world. Your life is in their hands, you may get wounded, die, or kill—and it will be at their orders, in their company. So the sense of betrayal is felt at a profound level that's difficult for any civilian to understand.

On my third trip to Virginia, on October 7, Jason has decided he's ready to turn himself in. He thinks it would be easier if I went with him. So the next morning we meet for breakfast at Waffle House in Dumfries. After eggs, toast, and many cups of coffee, I try to pay the check, but Jason keeps ordering refills. He's trying to pump himself up. "I want to try to be excited about this, as best as I can, you know? I don't want to go in there all miserable and grim and be like this is the end of the world." Finally, I convince him to get the last cup to go, and we drink it outside in the parking lot, where we get involved in a long discussion about the existence of God. Jason's concerned about my atheism. He doesn't want me missing out on heaven. The sun is high overhead when we finally get into the car and head toward the Marine base. "Man, this is gonna suck ass," Jason says, breathing deeply.

The MP stops us at the entrance, and after I explain Jason's situation, the Marine's face turns hard. He looks past me at Jason. "You deserted?"

"Yes, sir," Jason replies, looking miserable. To get to the Security Battalion, which houses the MP station, we have to drive a couple of miles down a tree-arched road, past a green, hilly golf course, and on through the woods. Jason is silent the whole time. He warned me that he would become almost comatose at this moment.

Inside the tiny lobby of the MP station, steps lead up to a windowed office, so the Marine on duty towers over us. This one is pure muscle, with shoulders and arms like tree trunks, a cinched waist, a smirk on his face, and a tattoo of Iwo Jima on his left bicep. He regards Jason with a combination of contempt and amusement, and keeps turning to the other two MPs in the office, saying something inaudible and then laughing. For some reason, the MP, who already has my driver's license, asks me my weight, age, and Social Security number before calling Jason to the window. Jason looks small and chubby, partly in comparison to the giant at the window, and partly because he is slouched into his boots. It is all "yes, sir" and "no, sir" from there on in. A blond MP comes out into the reception area, takes Jason's backpack, and commands him to say goodbye. We shake hands, but Jason can barely meet my eyes. And then he is gone.

Later he would tell me that the Marine sergeant who interviewed him was calm and professional, nothing like the MP at the reception desk. "If you don't want to help your brother Marine," he told Jason, "we don't want you." He didn't say it unkindly, just matter-of-factly.

If Jason is lucky, he'll be given nonjudicial punishment and released sometime in January with an other-than-honorable discharge; that is, in about three months from the day he surrendered. The Marines take forever to process people out—up to six months to be dropped from the rolls, and once you've returned, another three or four months to be processed out. At the Quaker House in Boston, they joke that the reason it takes the Marines so long to let anyone go is that "they just can't believe there's anyone out there who doesn't want to be a Marine."

The Army moves much more quickly. They have two out-processing stations, one at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, the other at Fort Knox in Kentucky. At Fort Sill, people are generally out-processed in three days because they mail your discharge papers to you. When Jeremiah arrived at Fort Sill, there were eight deserters. When he was sent home a week later, there were thirty. All of the National Guardsmen and reservists were returned to their units. Regular soldiers who left from their training units were getting released. Noncommissioned officers were facing court-martial.

At the Army's Fort Knox center, recruits aren't released until their discharge papers are personally handed to them, so the process can take two to three weeks. Of course, any of this can change at any time, which is why the people at the G.I. Rights hot line always counsel people to call right before they turn themselves in. In November things appeared to be backed up at Fort Knox. A soldier who was shipped from there to Fort Sill told Jeremiah that when he left, seventy AWOL soldiers and deserters were being held there.

AWOL and desertion are chronic problems; all any Army can hope for is to keep them at manageable levels, not to lose soldiers needlessly. The Army admits that youth, lack of a high-school diploma, coming from "broken homes," and having early scrapes with the law make a soldier only "relatively more likely" to go AWOL or to desert. In fact, the Army is careful to note, "the vast majority of soldiers who fit this profile are not going to desert." Yet the Army used that very same profile to try to identify potential deserters and give them extra attention—and the desertion rate, mysteriously, rose. It doesn't take a huge leap of the imagination to suppose that high-school dropouts and juvenile delinquents might have joined the military for a fresh start, a chance to succeed at something, and when they were instead tagged as potential failures and trouble-makers, they took off. None of the Army data comes close to capturing the hearts and minds of soldiers. What is any given person looking for when he or she joins the Army? Direction in life? A chance to belong to something? Father figures? An adventure with buddies or a test of manhood? Their parents' approval? And when they entered the military, what did they find? That they'd been given false promises by the recruiter? That the people they turned to for help threatened them or made idiotic speeches about Bible-carrying Iraqis? No help for depression? Or a lack of armor and ammunition on the battlefield? According to the Army's own study, before soldiers went AWOL, more than half of them sought help within the military—they spoke to their COs, to military chaplains, military shrinks. Apparently, to little avail.

The Army has examined the soldier, but not itself. It is tantamount to trying to understand the problem of teenage runaways without ever asking about their home life. Failure to adapt, issues with chain of command—there's no sense that the military culture and environment, the commanders, themselves, also play a part in driving soldiers out and away.

The Georgia Marine who thought he would be stationed in Kentucky made it all the way to his MOS training at Fort Leonard Wood, Missouri, before he took off. There, Jarred tried to get a foot injury treated and was told to take Tylenol. His pay was less than the recruiter had promised him, and he even seemed to be missing money from what he was paid. When he complained to his CO, he was told to shut up and mind his own business. Then he learned that his company was going to be deployed to Fallujah. "I ain't goin' to war," he told his sister flatly.

His sister kept telling Jarred to go talk to somebody. "Ain't nobody to talk to," Jarred told her. "Ain't nobody here interested." When he went home to Georgia on leave last March, he didn't return to his base. He made his mother and sister take down from the walls all their Marine paraphernalia, stripped the bumper stickers from their trucks, and refused to watch any movies or TV shows that featured the military. "The military," he said, "is a bunch of lies."

AWOL in America: